Reluctant Collaborator

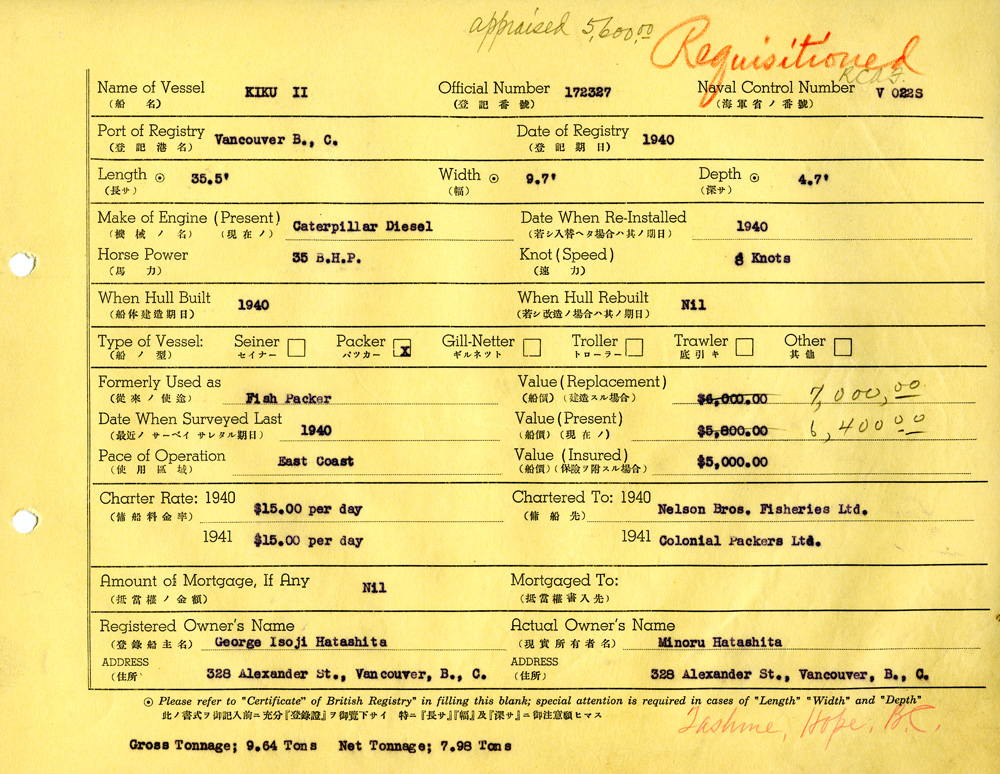

By December 12, 1942, 22,000 Japanese Canadians had been uprooted and interned. They were gone from coastal places like Vancouver. But not Kishizo Kimura. That afternoon, he stood on the platform of the Vancouver train station. He was waiting for the 1:15 train bound for the BC interior, where his family was interned. After a heavy snowfall and lengthy delay, he arrived to their Christina Lake internment site. Kimura had just returned from helping the government sell 950 fishing boats that it had seized from Japanese Canadians.

Along with every other Japanese Canadian, Kishizo Kimura was uprooted and interned. He lost his job and his personal property. He had to start again in a new place after the war. But his story is also unlike any other. Kimura agreed to serve as a member of two controversial committees that oversaw the forced sale of Japanese Canadian-owned property. He participated in the dispossession of his own community.

In the fall of 1942, Kimura advised government officials on the sale of fishing vessels. Three months later, he was invited to oversee the forced sale of all property still owned by Japanese Canadians in Vancouver. Kimura accepted once again.

Why did Kimura do what he did? Decades after his death, it is hard to say for certain. Some blame him for cooperating with a racist policy. Others think he made a wise decision. If the sales could not be prevented, perhaps his involvement helped to limit the injustice.

Kimura anticipated that one day his actions would be questioned. He wrote a memoir to explain his decisions and asked his children to donate it to an archive. In it, Kimura stresses that he was reluctant to get involved. He thought at first that the sales would be optional. He intended to help Japanese Canadian fishers get what they wanted for their boats.

Kimura’s memoir describes his concerns about the forced sales. He admits that other Japanese Canadians urged him to resign, but he wrote that he saw no better alternative. He worried that if Japanese Canadians failed to cooperate, they might cause increased “anxiety, fear, and even hatred.” He was “afraid of the current mood of the population in this time of war.”

When the homes of Japanese Canadians were listed for sale in the spring of 1943, Kimura finally resigned. He told the other members of the committee that he felt sick. Perhaps he had begun to doubt the usefulness of cooperation

Years later, Kimura still defended his actions. In his memoir, he argued that choices like his allowed Japanese Canadians to become full citizens. He praised cooperation with discriminatory Canadian law, even with internment. Japanese Canadians, he said, “were rewarded for their struggle and finally reached the dawn of a new era after the war.” Then other Canadians “realized that past discrimination was unjust. They gradually came to know the true value of Nikkei people.”

According to Kimura, the suffering of his generation paid off. His own cooperation with racist policy, he suggested, was really a kind of resistance.

Nikkei National Museum, 2011.79.4.1.1.36

Nikkei National Museum, 2011.79.4.1.1.36

Nikkei National Museum, 2019.4.4.1.341

Nikkei National Museum, 2019.4.4.1.341