Perishable Property

The person most responsible for justifying the dispossession of Japanese Canadians was a bureaucrat named Glenn McPherson, the founding Director of the Vancouver office of the Custodian of Enemy Property. The son of a judge and a lawyer himself, McPherson wanted a justification that could withstand a legal challenge. Also, although he held racist views, he knew that not everyone could be convinced to dispossess innocent people simply because they were “of the Japanese race.”

John Erskine Read, for example, helped to write the internment policy. Still, he felt that “any measure which takes a Canadian citizen, born in this country and in respect of whom there is no proven disloyalty, and against his will deprives him of his status as a Canadian citizen … runs contrary to principles which I have always regarded as fundamental in our constitution.” For Read to participate in perpetrating this very injustice, he had to be able understand the policies as legal and fair.

McPherson accomplished his goal by turning a law written to protect Japanese Canadians against them. Law required the Custodian to protect the interests of Japanese Canadians. It held property ‘in trust’ for them. In carrying out this duty, the Custodian was permitted to sell property that declined in value over time, such as grocery stock. Apples rotting on a shelf are of no value to their owner.

In late 1942, McPherson began to argue that all of Japanese Canadians’ property was declining in value and could be sold, irrespective of the wishes of its owners. All of their property – their homes, businesses, farms, pots and pans, family heirlooms – was like grocery stock, said McPherson.

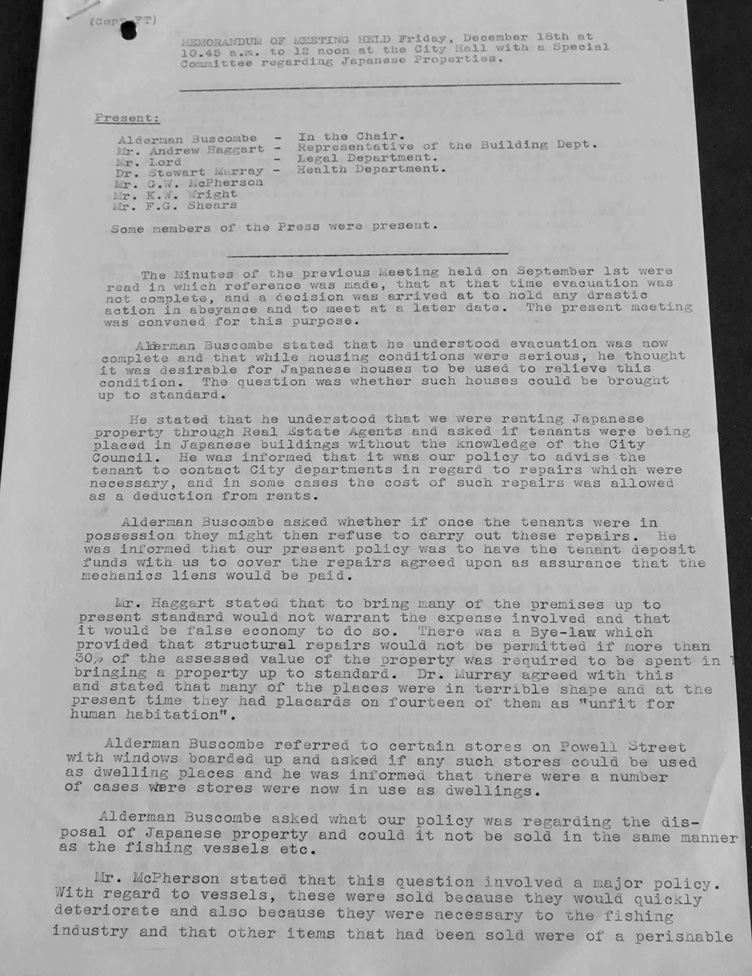

To support this claim, he drew on the arguments of others. The city of Vancouver wanted to bulldoze the former Japanese Canadian neighbourhood near Powell Street to build new housing in its place. City inspectors claimed the area was unfit for human occupants. If they could not be rented out, the properties would amass debt and decline in value. McPherson did not give city officials the properties they desired, but he did make careful note of their arguments.

Meanwhile, McPherson was in conversation the Soldier Settlement Board, a federal office that provided land to veterans. Those officials claimed that Japanese Canadians’ farms were falling apart without their owners. Renters, they said, neglected harvests and let the farms deteriorate. McPherson saw a pattern developing.

His final source was his own staff. They claimed that it was impossible to protect Japanese Canadians’ personal belongings. Countless items were being lost, stolen, and destroyed. It would be much better, staffers argued, to sell the belongings and give Japanese Canadians the cash.

McPherson drew these concerns together into a single argument for forced sales. “It is obvious,” he wrote, “both in the city and country, that the Japanese property is going to deteriorate rapidly.” From the perspective of both government officials and the Japanese Canadian owners, he said, the best policy was to sell everything.

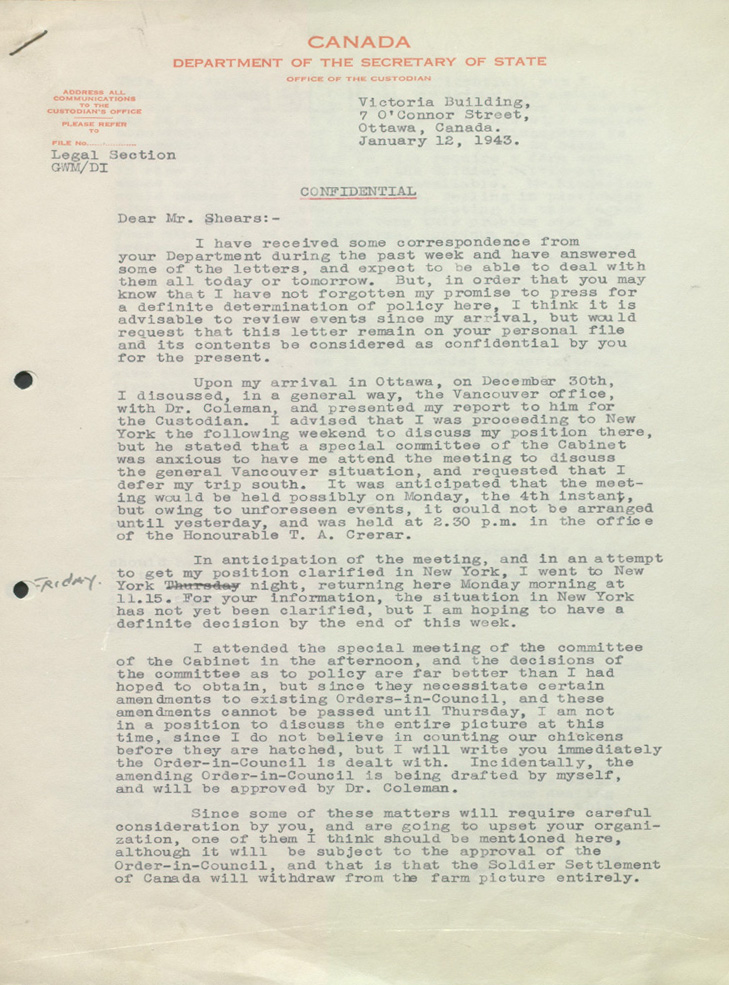

These claims were false. The property was not deteriorating in the ways that he said. Still, the argument worked. Ignoring the protests of property owners, he convinced cabinet to force sales. Cabinet authorized the dispossession with Order in Council 469 on January 19, 1943. This result, McPherson wrote to a colleague, was “far better than [he] had hoped to obtain.”

The forced sale of everything soon began.

Library and Archives Canada, RG117, volume 2536, file 59008 Part 1.1

Library and Archives Canada, RG117, volume 2536, file 59008 Part 1.1

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, F.G. Shears Papers, box 2, file 2

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, F.G. Shears Papers, box 2, file 2