The Compensation Debates

Once the Second World War ended, Canadians increasingly realized that the dispossession had been wrong. Civil liberties groups joined Japanese Canadians in protest. Newspapers took up the cause. Opposition parties demanded that the government take action.

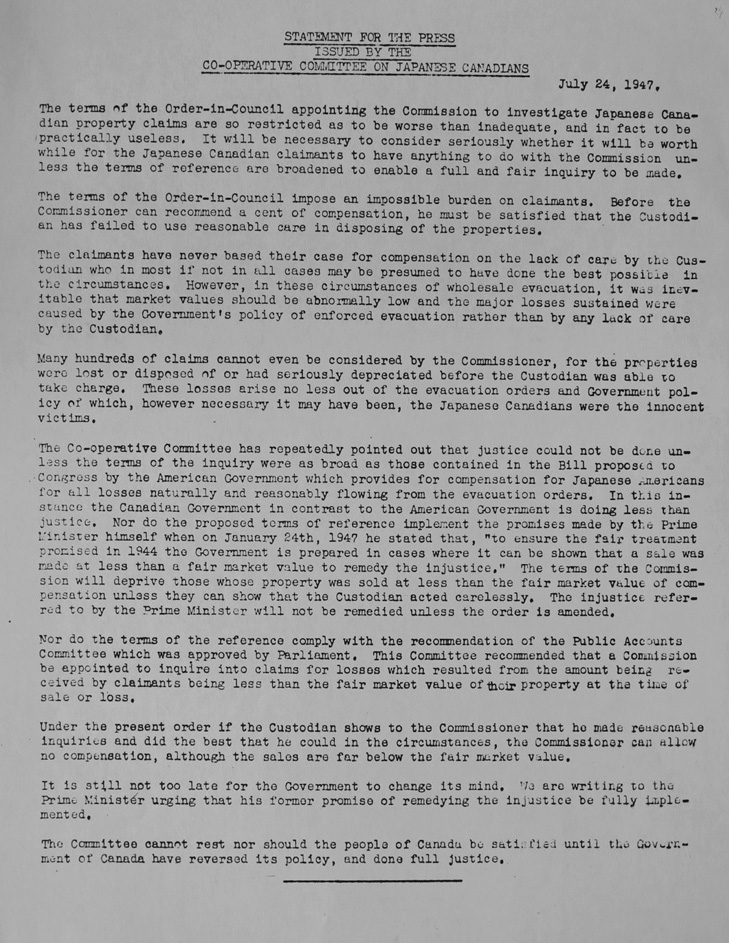

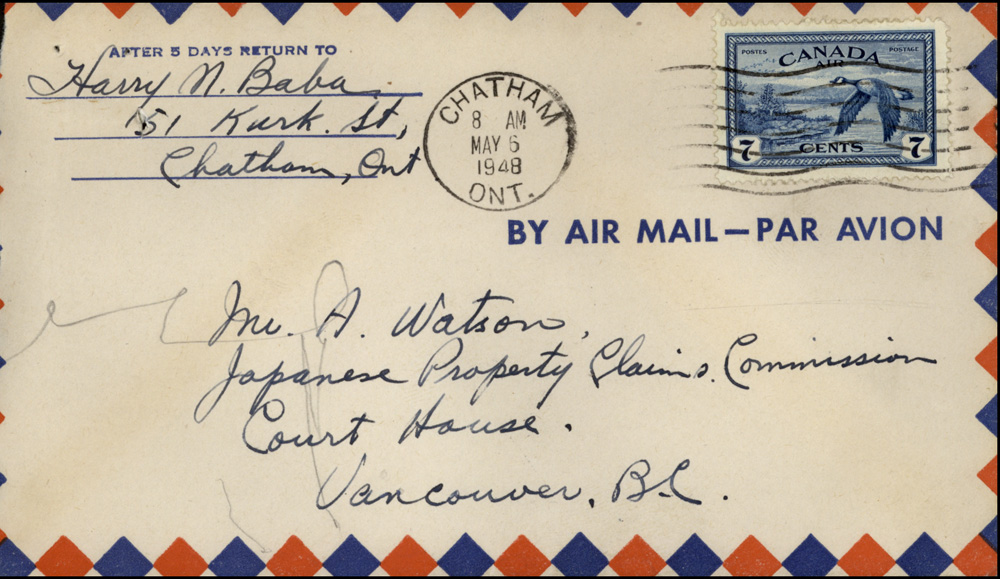

In response, the prime minister established a Royal Commission to investigate Japanese Canadians’ claims that they had suffered unfair losses. Led by Justice Henry Irving Bird, this inquiry was known as the Bird Commission.

Still, deep disagreements persisted. What was the nature of the injustice that had occurred? Japanese Canadians and the government had very different answers.

Government officials maintained that their policies had been lawful and sound. But, given the administrative challenges of the internment, officials admitted that not everything had gone according to plan. Some property had sold, they knew, for less than it was worth. The Bird Commission, they argued, should compensate Japanese Canadians for errors made in executing a policy that was basically fair and well intentioned.

Japanese Canadians knew that the injustice of the dispossession ran far deeper. Their property, they felt, should never have been seized and sold. They had suffered as a result of a government acting in bad faith. Their homes, many felt, had been stolen. They saw the dispossession as part of the larger harms of the internment.

In the end, the commission was designed to disappoint Japanese Canadian claimants. At the hearings, Japanese Canadians were often silenced. Their arguments about a larger injustice were off topic, they were told.

In their testimonies, Japanese Canadians held the government to a standard that it was not prepared to meet. They voiced an alternative understanding of the sources of injustice and the compensation that was their due.

Library and Archives Canada, MG30 C-160, file "Thompson, Grace 1"

Library and Archives Canada, MG30 C-160, file "Thompson, Grace 1"

Library and Archives Canada, e011179273-047

Library and Archives Canada, e011179273-047