Background

How do you teach intermediate-age students about the internment and dispossession of Japanese Canadians?

Scroll down

Scroll down

What kind of activity could we do where students would get excited about the concepts around dispossession?

We use a simulation.

Below is a snapshot of the simulation. For the full description of the activity, visit the Main Dispossession Activity page.

Students make a hand-drawn community of a Japanese Canadian neighbourhood on a classroom bulletin board. They populate their properties with people and possessions which they pin into their homes and businesses. (Hands-on learning)

Because of the work students put into their hand-drawn community, the people and the belongings, they become very attached to their work. (Hearts-on Learning)

Then, over time, after students have built up sufficient possessions, Canada and Japan go to war with each other, and the Japanese Canadian avatars/characters from the Powell Street displays are moved to an internment camp bulletin board. Then, as the incarceration of Japanese Canadians continues, the possessions left in the Powell Street display start to disappear.

As a class, the students process how this happened, why this happened, and what the repercussions were. (Minds-on learning)

Foreword by Miriam Miller

Landscapes of Injustice (LOI), provides learners with opportunities to engage in rich and meaningful explorations of a dark time in Canadian history while provoking deep reflection, critical thought, historical empathy, and compassionate action. Landscapes of Injustice weaves Social Studies content with personal and social responsibility; aspects of social and emotional learning (SEL) are embedded within lesson content and activated through learning activities.

Through various learning activities (e.g., discussions, games, journals), students recognize their own and others’ thoughts and biases, emotional reactions, and actions. Students keep a reflection journal which helps build personal and social awareness and responsibility; the journal documents growth and development of understanding in both the Social Studies content and SEL skills. Given this time in history, the curriculum develops historical empathy skills, by building emotional vocabulary and understanding as students explore emotions such as sorrow, despair, shame, loneliness, and confusion. Students engage in perspective taking, an essential element of empathy, as they imagine different experiences from a Japanese Canadian’s perspective (e.g., through the storyboard/Powell Street simulation activity). Perspective taking is a cognitive skill that enhances both empathy and critical thinking. Critical thinking skills are embedded and activated as students puzzle through challenging issues related to race, equity, and inequality. Many of the reflection questions and activities allow students to deepen their understanding of their own positionality and bias while exploring Canada’s past (and current?) biases, racism, and prejudice, which develop intrapersonal skills such as self-awareness and metacognition. Finally, as students explore the notion of redress, they are prompted to consider how their sense of empathy might motivate them to act to support the UNCRC (i.e., compassionate action). The unit can be used to introduce themes of social justice, race, and equity and can serve as a foundation on which to consider other times of racism/prejudice in Canada’s past and present. Ultimately, LOI is designed to develop insightful, compassionate, and empathic citizens – a beautiful combination of head, heart, and hands (heart and mind education/hands-on, hearts-on, minds-on education).

Note: In this resource, SEL is infused throughout the content (nature of the content) and also through the activities (cooperative learning, reflective journals, etc.).

Miriam Miller is an educator and researcher passionate

about social and emotional learning (SEL). Miriam supports

educators in ongoing professional development as they

consider how to embed SEL into learning activities in

various subject areas and across all disciplines.

Miriam Miller is an educator and researcher passionate

about social and emotional learning (SEL). Miriam supports

educators in ongoing professional development as they

consider how to embed SEL into learning activities in

various subject areas and across all disciplines.

Why Teach About the Internment and Dispossession of Japanese Canadians?

The internment of Japanese Canadians is a black mark on the history of a nation that prides itself on its ethnic diversity and multicultural policies. A study of the internment of Japanese Canadians raises many questions about human nature, racism, discrimination, social responsibility, and government accountability. Our democratic institutions are not infallible nor are they easily sustained. Silence and indifference are the enemies of a healthy working democracy. Through the study of the internment, students will come to understand that civil liberties can only be protected in a society that is open and in a democracy where its citizens participate actively to protect the rights of others.

The internment of Japanese Canadians was not an accident or a mere coincidence of wartime decisions made under duress or out of necessity. Life-altering decisions were made with little regard to the guilt or innocence of the victims. The individuals that made these decisions were unable or unwilling to assess the issue without bias or prejudice. Many Canadians reacted with indifference and did little to oppose the actions of the government.

Throughout this unit students will be asked to recognize and question their own biases so that in the future they will not easily fall prey to the stereotyping and over generalization which our leaders in the winter of 1942 used to justify their acts.

It is expected that students will develop a much broader understanding of human rights and why they are important. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and other human rights legislation enacted since 1942 cannot ensure that future generations will not suffer such acts of discrimination. A well-educated, caring citizenry living in an open and just society will provide the best measure of protection against the insidious nature of stereotyping and racism.

This unit covers many of the learning outcomes of the intermediate Social Studies curriculum, Historical Thinking Concepts, and Social Responsibility including:

- content information about the internment of Japanese Canadians and the knowledge of significant consequences for many families in British Columbia;

- an understanding of issues of human rights, racism, discrimination, and the redress of Japanese Canadians, as a means of realizing how easily stereotyping happens and how dangerous it may be to remain silent;

- a foundational springboard from which to study other cultures that form our multicultural Canada of today.

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions about Internment and Dispossession

Why were Japanese Canadians put into camps?

Officials alleged that the internment was a "necessity" of the Pacific War. However, neither the army nor the RCMP saw Japanese Canadians as a threat. Prime Minister Mackenzie King stated in the House of Commons in 1944:

It is a fact that no person of Japanese race born in Canada has been charged with any act of sabotage or disloyalty during the years of war.

The internment of Japanese Canadians can be explained by the racism of the time.

Since Canada was also at war with Germany and Italy, why weren't Canadians of German and Italian descent put into camps?

A comparatively small number of Germans (847) and Italians (632) were interned. These were individuals suspected of some sympathy or connection with Germany and Italy, with whom Canada was also at war. In contrast, every Japanese Canadian in Pacific Canada (22,000 people), including children and those who had fought in Canada’s armed forces in World War I, were uprooted from their homes and interned.

Weren't the camps justified because Japan bombed Pearl Harbor?

No. Canadians of Japanese descent had nothing to do with Pearl Harbor. Over half of those incarcerated were Canadian by birth and more were naturalized British subjects.

But in a time of war, doesn't everyone suffer?

The incarceration of innocent citizens was a gross violation of civil rights. There was no due process of law – no charges, no trials. People were assumed to be guilty on racial grounds alone.

What happened to their homes and possessions?

When they were forced from their homes, Japanese Canadians were told that they could take with them only what they could carry (150lbs/68kg for adults and 75lbs/34kg for children). Their homes, businesses, farms, furniture, and other possessions were to be held for safekeeping by the "Custodian of Enemy Alien Property" who subsequently sold everything without the owners’ consent and at a small percentage of their prewar value. When restrictions were lifted in 1949, four years after the war, Japanese Canadians had to start all over again. They had no homes to return to.

Cautions and Guidelines

- Do not teach controversial topics at the beginning of the year. First, build a relationship with the class and establish a safe, respectful environment for all learners.

- This resource is designed to facilitate instruction on topics related to the history of Japanese Canadians. The history of Japanese Canadians is a record of facts. However, it is important to recognize that topics such as the racism, the internment, and the fight to obtain redress may be sources of sensitivity or controversy. Teachers must also be aware of their own biases.

- Students of Japanese Canadian heritage may experience an emotional reaction when learning about or discussing the racism leading to the internment. It is important not to assume that students of Japanese Canadian heritage are any more knowledgeable about their family history, culture, or language than students of other backgrounds.

- Avoid stereotyping. Cultures evolve over time and what is applicable or descriptive of Japanese culture is not necessarily the culture of all Japanese Canadian individuals.

- Survivors of the internment and other Japanese Canadian people may have painful memories to share, and while they may feel hurt or anger, they also have the strength to share their feelings with others in order to promote healing and understanding.

Notes on Curriculum Connections and Assessment

Notes on Curriculum Connections

Each lesson includes a chart (located under the heading “Why”) which outlines possible learning outcomes for students.

BC educators will undoubtedly recognize the language of our Revised Curriculum in both the learning outcomes and assessment sections of this unit. We hope educators outside of the province will also find the charts relevant, helpful, and user friendly. We believe that – regardless of the curriculum language used – all educators seek to cover content and foster opportunities for their students to practice and develop essential skills. Accordingly, we have included a total of 4 sections in each lesson chart.

The first section, labelled “Know” addresses curriculum content. The second section, labelled “Do” focusses on the six historical thinking concepts referenced in the curricular competencies for Social Studies. The third section of the chart addresses “Core Skills” or core competencies, often referred to as life skills as students need these throughout education and beyond. Finally, the fourth section focusses on the First Peoples’ Principles of Learning (FPPL), which help ground our teaching more authentically in the values and experiences of Canadian Indigenous Peoples.

At first glance, the charts may appear overly “robust”; however, they are not meant to be overwhelming or to suggest educators need assess all components. In fact, formal assessment is really limited to the first two sections of “Know” and “Do.” We have tried to limit learning outcomes in these sections, thus allowing teachers to zoom in on a manageable number to assess. Teachers are encouraged to focus on just one outcome per section, but this, of course, is up to the individual.

It is worth noting that the content and competencies included in the charts are by no means exhaustive, and educators may find others that better fit their needs. Finally, as mentioned, the last two sections of “core skills” and “FPPL” are not formally assessed but rather are guideposts to inform your teaching practice and enhance student learning and development.

Notes on Assessment

This unit seeks to offer teachers some possible tools for formative and authentic assessment. Ideally, these assessment tools not only help educators assess student learning but, as importantly, help guide teacher instruction and inform students of their personal learning journey. Teachers are encouraged to focus on just a few learning outcomes found in the “Why” chart. From there, teachers can then choose from the tools below that best align with these learning outcomes.

The main tools of assessment for this unit include:

- Journal Reflections: Students are given multiple opportunities to record their thoughts and questions, which allow them to reflect on what they have learned and to synthesize their understanding. Journal reflections also offer students an opportunity to express their feelings and make connections to their personal lives. Possible reflection questions can be found at the end of lessons under the subheading: Suggested Journal Reflection Prompts.

- Discussions: Students are encouraged to actively participate in whole class and small group discussions throughout the unit. Teachers may choose to include strategies such as “Think, Pair, Share” to engage all students and generate deeper thinking. Possible discussion questions can be found at the end of lessons under the subheading: Suggested Discussion Questions.

- Observations: Student are observed during various activities and group interactions. Teachers may choose to consider students’ core skills during these observations.

- Other: There are several tasks that can be used for more formal assessment. Teachers are encouraged to co-construct criteria with students in order to deepen the students’ understanding of learning outcomes.

Please Note: Teachers are encouraged to consider other formative assessment tools to ensure all learners are given an opportunity to show their learning, such as informal one-to-one conferencing or having learners sketch a picture in lieu of writing a journal reflection.

Assessment options

There are two assessment options available that teachers could use:

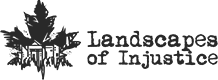

Assessment Rubric

Teachers may choose to use this rubric throughout the unit based on discussions, journals, conferences, etc. Teachers may also wish to copy-paste a section from this rubric for marking specific assignments.

- Photocopy the Assessment Rubric for each student

- Highlight appropriate boxes

- Add comments to support student progress and learning

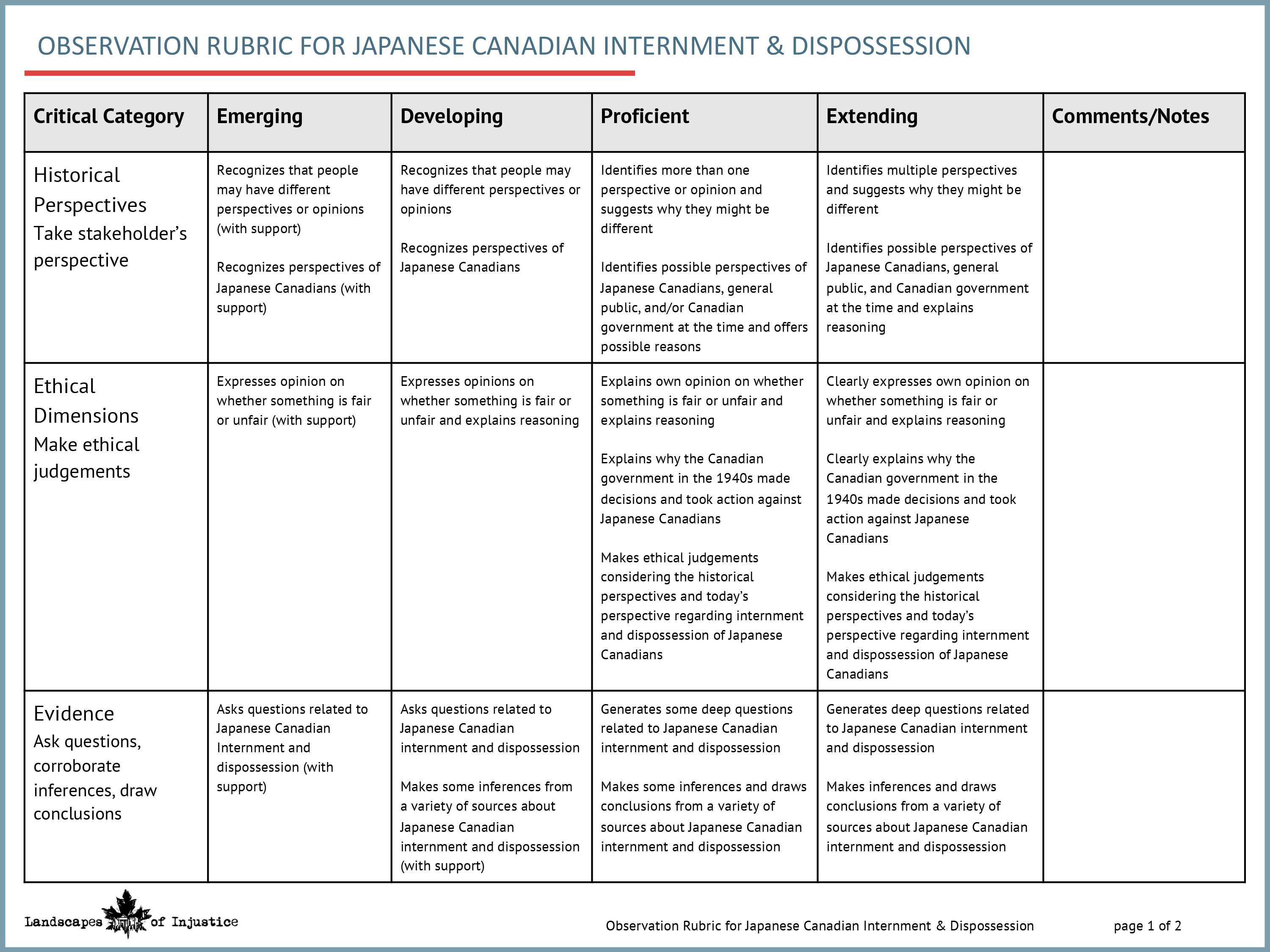

Assessment Framework

Similar to the rubric, this tool could be used for a comprehensive assessment throughout a unit or segmented into sections for marking specific assignments. The prompts “What’s working?” “What to consider?” and “What’s next?” target assessment for learning.

- Photocopy the Assessment Framework for each student

- Highlight along proficiency scale or write word (emerging, developing, proficient, extending) inside each comment box

- Add comments using prompts to support student progress and learning

Glossary

- bias

- A mental tendency, preference, or prejudgment. Could be positive or negative.

- censorship

- The action of suppressing in whole or in part something that is considered politically or morally objectionable. Letters written by Japanese Canadians were opened, read, and in many cases pieces were blacked out or cut out. Delivery was delayed and free discussion between friends and family members who were separated was inhibited. The contents of the only English language Japanese Canadian newspaper The New Canadian had to be approved by a censor before going to press.

- curfew

- A police or military regulation requiring persons to keep off the streets after a designated hour. A proclamation on February 26, 1942 restricted all Japanese Canadians to their homes from sunset to sunrise within the 100-mile protected area on the coast of BC. The RCMP enforced restrictions on personal freedom.

- discrimination

- Actions resulting from a particular mindset or prejudice. A means of treating people negatively because of their group identity. Discrimination may be based on age, ancestry, gender, language, race, religion, political beliefs, sexual orientation, family status, physical or mental disability, appearance, or economic status. Acts of discrimination hurt, humiliate, and isolate the victim.

- dispossession

- Refers to the range of processes that led to the loss of Japanese Canadian owned property, including theft, vandalism, neglect, and forced sales.

- enemy alien

- An alien (foreigner) living in a country that is at war with his country of ancestry.

- espionage

- The work of spies. Politicians and some people in British Columbia said that Japanese Canadians would not be loyal to Canada and would become spies and saboteurs. The RCMP and the military said that their investigations found no evidence to support such a claim. Nevertheless, the internment was carried out as a “security precaution.”

- evacuation

- This was a term used by the government to justify its uprooting and internment of Japanese Canadians. It implied that Japanese Canadians were removed from the Pacific Coast as a matter of their protection.

- Although this term is still used by community members and others describing this history, we suggest that uprooting and internment are better terms for these events.

- exile

- To force a person to leave one’s country, community, or province as punishment. Banishment. Japanese Canadians were forced to leave the coast of British Columbia and later were told to prove their loyalty by moving “east of the Rockies” or be “repatriated” to Japan, a country many had never seen.

- franchise

- The right to vote. Japanese in Canada were denied the franchise in provincial elections until 1948 and in federal elections until 1949.

- incarceration

- To be put in prison. Japanese Canadians were incarcerated in prisoner-of-war camps and in internment camps.

- in trust

- To hold something in safekeeping for another person. All property (real estate, businesses, cars, machinery, etc.) confiscated during the internment, was given “in trust” to the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property for safekeeping under the powers granted in March 1942. This property was later sold without the consent of Japanese Canadians.

- internment

- Refers, in this context, to the period during which Japanese Canadians were barred from Canada’s Pacific coast. This usage follows the Oxford English Dictionary definition of the verb “to intern” as the act of confining people “within the limits of a country, area, or other place, esp. for political or military reasons; spec. (originally) to oblige (a person) to reside within prescribed limits.” The internment of Japanese Canadians began December 1941, when the government first uprooted Japanese Canadians from coastal British Columbia, and ending in April 1949, when the government finally lifted the prohibition on their return to the coast. During this time, thousands of Japanese Canadians lived in purpose-built camps, but many others lived and moved across varied sites across Canada.

- issei (ees-say), nisei (nee-say), sansei (sun-say), yonsei (yon-say)

- Japanese language terms used to describe first, second, third, and fourth generation settlement in Canada.

- Nikkei (neek-kay)

- Means ethnically Japanese. Nikkei Kanadajin means Canadian of Japanese ethnicity.

- prejudice

- A predetermined judgment that is not based on the facts of a given circumstance or situation. Often used to describe a negative attitude directed toward a person or an entire group of people. Prejudiced thinking may result in acts of discrimination.

- propaganda

- The systematic effort of controlling public opinion or a course of action by using selected facts, ideas, or allegations.

- protected area

- An area extending 100 miles (about 160 kilometers) from the coast of BC to the Cascade Mountains was deemed a secure area. This designation was a step that led to the uprooting of Japanese Canadians from coastal settlements in BC.

- racism

- Racism may be systemic (part of institutions, organizations, and programs) or part of the attitudes and behaviour of individuals. It contributes to unequal distributions of opportunities and resources on the basis of race. In the past, including during the 1940s in Canada, racist policies and laws were explicitly supported by an ideology that saw the world as separated into separate and competing races. Today, racist inequalities can persist even when most people no longer believe these ideas because patterns entrenched historically can still be perpetuated.

- redress

- Refers to the movement within the Japanese Canadian community for an official acknowledgement of wrongdoing and financial compensation from the federal government in 1988. Under Prime Minister Mulroney the Government of Canada gave an official apology for the injustices it had enacted upon Japanese Canadians and announced a financial compensation package.

- resettlement

- At the end of the war, Japanese Canadians were strongly pressured to establish themselves outside of British Columbia. More than 9,000 Japanese Canadians made new homes in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario. The policy was designed to disperse those of Japanese ancestry throughout Canada. However, the federal government failed to recognize that Japanese Canadians were not welcome in Moose Jaw any more than they were in Vancouver, and were being sent to another hostile environment. Not until 1949 were Japanese Canadians allowed to return to the “protected area” within 100 miles (160 kilometers) of the Pacific Ocean.

- restitution

- The act of making good for something that is lost or taken away. Japanese Canadians were deprived of their possessions, livelihood, rights, and freedoms from 1941 to 1949. They were victims of injustices and were seeking restitution for those wrongs.

- sabotage

- An act to deliberately damage or destroy something, carried out clandestinely in order to disrupt the economic or military resources of an enemy. Politicians and some people in British Columbia suspected that Japanese Canadians would not be loyal to Canada and would become spies and saboteurs. There is no evidence that this ever happened. Prime Minister Mackenzie King said in the House of Commons, August 4, 1944, “It is a fact that no person of Japanese race born in Canada has been charged with any act of sabotage or disloyalty during the years of war.”

- stereotyping

- The formation of belief(s) about a person or groups of people that does not recognize individual differences. Stereotyping may be positive or negative in character.

- Uprooting

- Refers to the government decision to expel Japanese Canadians from their homes and communities in 1942. Many historians and community members also refer to a “second uprooting” in 1944–1945 when Japanese Canadians were forced to choose between exile to Japan and relocation to Eastern Canada.