Broken Promise

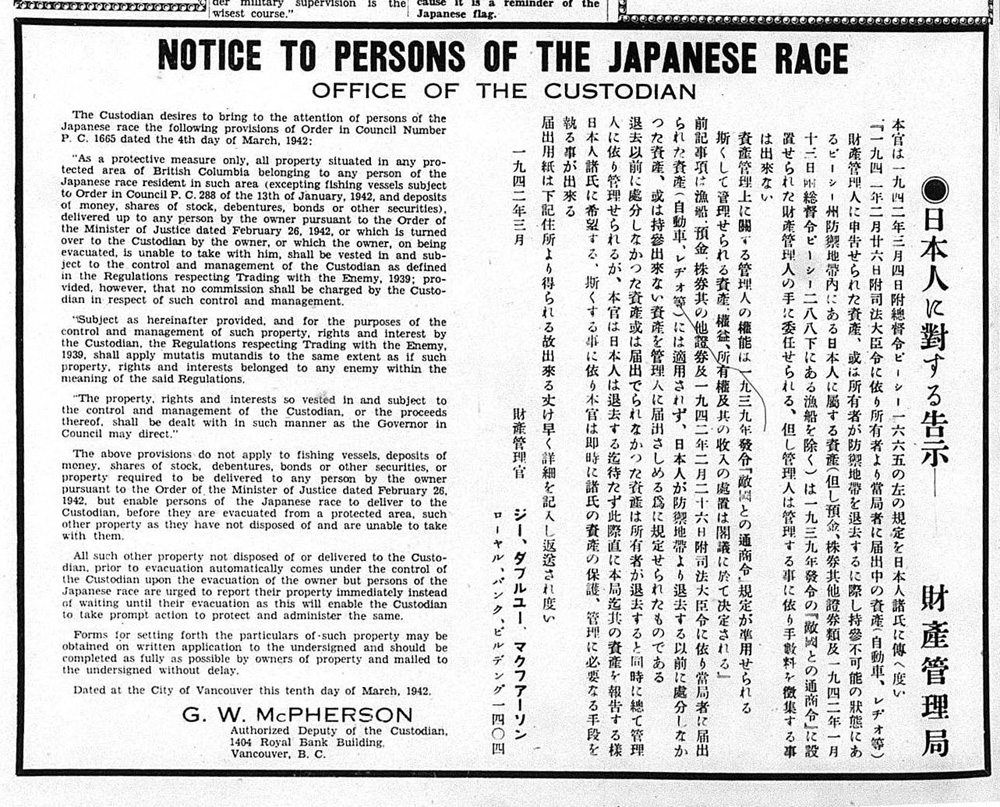

When Japanese Canadians were forced from their homes, the government promised to preserve their property for them. Everything was supposed to be returned at the end of the war. In 1942, The government placed a notice in the community newspaper, The New Canadian: “The whole purpose of the custodian’s taking over the property is in order that it may be properly protected.”

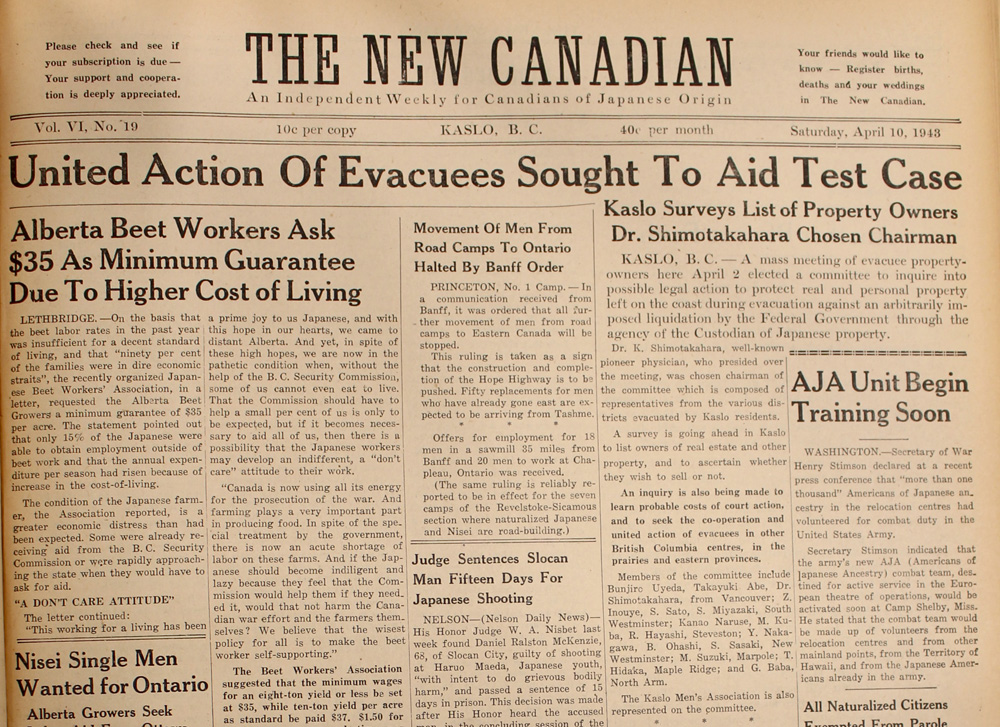

This promise of protection was betrayed a short time later. In the spring of 1943, the government decided to sell everything that Japanese Canadians had been forced to leave behind. When they learned of this policy, many Japanese Canadians organized a court challenge. They hoped to prove that the forced sales were illegal.

Japanese Canadians interned in Slocan, New Denver, and Kaslo established the Amalgamated Property Owners’ Association (APOA). Its chairman was Dr. Kozo Shimotakahara, interned in Kaslo. Japanese Canadians pooled their money to hire the Vancouver law firm of Norris and MacLennan.

The APOA instructed its legal counsel to challenge the policy at the Exchequer Court of Canada. The forced sales, they argued “cast aside the rights of a citizen.”

The APOA chose four people to represent their challenge. Eikichi Nakashima was born in Japan but had become a naturalized British subject. Before the internment, he had worked as a fish buyer for BC Packers and lived in the Powell Street district of Vancouver with his wife and eleven-year-old son, Shinji.

Tadao Wakabayashi was born in Vancouver and so was a citizen by birth. Before the war, he had made his living as a truck driver. He and his wife Akiko sought to prevent the sale of their home, dishware, and one “pair ice skates,” among the long list of their personal property seized by the Custodian.

Jitaro and Takejiro Tanaka were both Japanese nationals residing in Canada. Takejiro lived with his wife, Ayako, and four children under the age of 10. His possessions included war bonds in the names of his children.

On May 29, 1944, Nakashima v. Canada was heard at the Exchequer Court in Ottawa. The lawyer for the Japanese Canadian litigants, J. Arthur MacLennan, put forward two key claims.

First, the special authority of the government during wartime had limits. The government could only undertake actions that had clear connection with the war effort. Taking property from Japanese Canadian had no connection to wartime security.

Second, MacLennan argued that the government was bound by its promise to protect the property of Japanese Canadians. The forced sales, he said, were clearly not in the best interests of the owners.

On August 28, 1947, Justice Joseph Thorarinn Thorson finally ruled on the case, more than three years after its hearing. In that time, the government completed almost all of its sales, and the Second World War had ended.

Thorson decided in favour of the government. The Japanese Canadians lost. He agreed with all of the arguments raised by government but decided the case on the basis that the Japanese Canadian litigants had used the wrong process in bringing the matter to court. Ultimately, Japanese Canadians in the 1940s had no viable legal path by which to make their case. They would wait decades for the government to finally acknowledge this wrongdoing.

The New Canadian, 12 March 1942

The New Canadian, 12 March 1942

The New Canadian, 10 April 1943

The New Canadian, 10 April 1943