Lesson 3:

DISPOSSESSION

Scroll down

Scroll down

Intro Story: The Tagashira Family

Visit our Timeline

Rinkichi Tagashira made special arrangements to protect his Vancouver business, the Tagashira Trading Company, from government control. The business had allowed Tagashira to buy a home and other investment properties. In 1942, he, his partner Masue, and their two children looked toward a hopeful future.

When they heard that they would be uprooted, the family acted quickly. Masue boxed up their belongings and locked them in their attic. Tagashira placed the Company under the temporary ownership of a former employee, James Y. Lim.

At first, the arrangement was successful. It kept the Tagashira Trading Company out of government hands for two years. The profits provided the family with some additional spending money in the internment. Tagashira planned to return to the business when the ordeal ended.

The government pressured Tagashira to sell, but he held firm. Then in 1944, Rinkichi was outraged to learn that his store manager intended to allow the government to seize the company. Key suppliers had boycotted the store because it was still Japanese-Canadian owned. Government officials argued that it would fail because its Japanese-Canadian customers were interned. Lim believed that the business would soon fail.

Tagashira was not convinced.

“My manager and I are making money not losing,” he wrote. He did not believe that the plan to sell his sole source of income was in his “best interest.” He sent repeated letters protesting the sale.

But his protests were of little use. His store was sold without his permission. His family’s personal belongings from the attic were auctioned off at 25 cents a box. The government sold his business for a mere fraction of its worth.

The Lesson

Lesson Overview

Allotted Time: 7 PERIODSStudents investigate the change in government policy, with respect to the property of Japanese Canadians, from one of custodial trusteeship, to one of forced sales. Students examine the causes of the change in policy and then assess whether the change was made in good faith. The lesson concludes by examining reactions from Japanese Canadians to the forced sale of their property and the responses from the Custodian of Alien Property.

Access this lesson online by selecting an Activity from below, or print this lesson package in full by clicking here.

Focus Question

Was the government’s decision to liquidate Japanese Canadian property made in good faith?

Targeted Learning

- Analyze changing government policy regarding Japanese Canadian owned property

- Understand and assess the role of bureaucrats, Japanese Canadians and public opinion in the change of policy from trusteeship to forced sales

- Understand the complexity, motivations, rationales, and fluidity of the decision to dispossess Japanese Canadians of their property

- Understand the implicit ethical underpinnings of making a promise and acting in good faith

- Assess government policy and make an ethical judgment. Was government action valid, reasonable, respectful, and proportional in light of the issues of the day?

- Understand the tools and means with which Japanese Canadians protested the forced sale of their property

- Assess government response to the protests of Japanese Canadians and the processes available to them for compensation

Activities

Four Corners Activity

Do you trust your government? Would you expect the government to do the right thing? This activity asks students to consider those questions among others as a lead-in to a much deeper examination of the role of government in the forced sale of Japanese Canadian owned property.

Four Corners Activity

Think About It! Activity

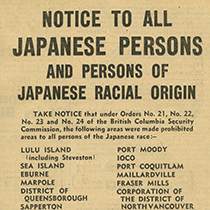

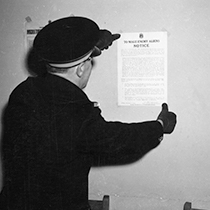

In this activity we will examine the connection between the War Measures Act and the enactment of many Orders-In-Council which impacted the lives of Japanese Canadians after Canada declared war against Japan in 1941. Groups will discuss two pieces of legislation and consider the reactions within the Japanese Canadian community.

Think About It! Activity

Voices of Protest Activity

The policy of forced sales evolved slowly and was enacted through a series of steps through Orders-in-Council (O.I.C). O.I.C. PC 1665 began the shift toward wholesale forced sales but did not enact it, while O.I.C. PC 2483 strengthened the promise to protect the property of Japanese Canadians in the midst of uprooting and internment. Japanese Canadians had concerns about the safeguards being taken for their property. Concerned with the potential for unrest, disobedience and an orderly uprooting the government enacted O.I.C. PC 2483. This lesson examines that enactment.

Voices of Protest Activity

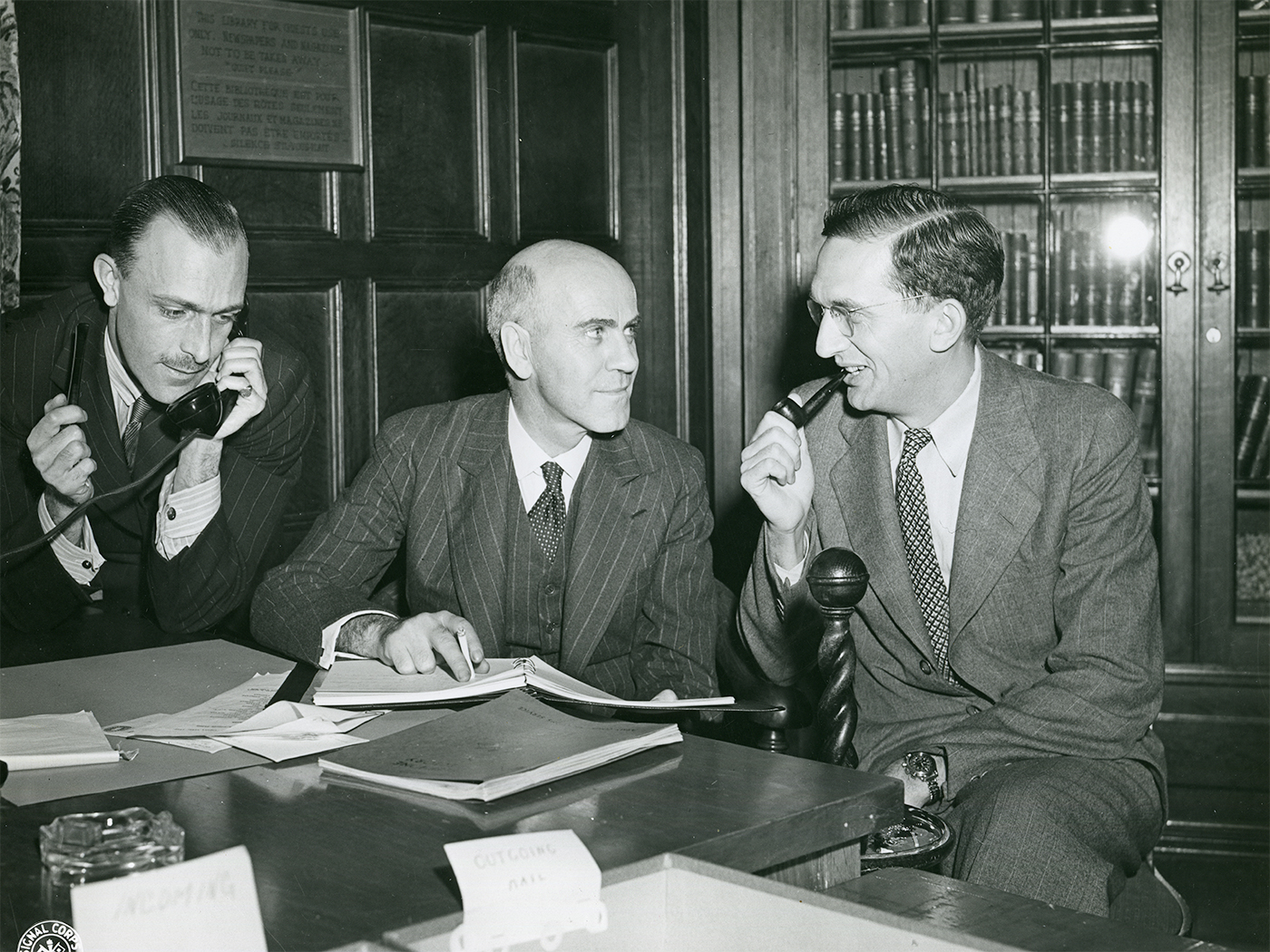

Viewpoints on Dispossession Activity

Opinions on what to do with Japanese Canadian owned property varied greatly both within and outside government circles. In this activity students learn that there were a number of complex viewpoints behind the decision to forcibly sell Japanese Canadian property. The goals of federal, provincial, and municipal politicians and bureaucrats factored significantly in the evolution of policy.

Viewpoints on Dispossession Activity

A Promise Broken

Using multiple sources and presenting a variety of perspectives, students address the question of why government policy changed from trusteeship to the forced sale of Japanese Canadian owned property. Students will be provided with archival evidence from government bureaucrats, Japanese Canadians, and In-betweens (agents, lawyers, auctioneers, and the media). Students apply evidence gathered from these sources in an attempt to answer two questions: (1) What were the causes for the change in policy? (2) Was the decision to change policy made in good faith?

A Promise Broken

The Community Responds: Letters of Protest Activity

During the 1940s, Canada enacted mass displacement of people and dispossession of property on racial grounds — a collective moral failure that remains only partially addressed. Japanese Canadians lost their homes, farms, businesses, as well as personal, family, and communal possessions. This series of activities engages students in reading and reflecting upon the many voices that protested the forced sales. Students will also encounter responses from the Custodian and consider how many families were impacted permanently by the loss of property, income, place, and future.

The Community Responds: Letters of Protest ActivityEvaluation

Assessment will be left to the individual instructor and may incorporate the assessment rubrics provided with this resource.

Handouts

- Handout 3.1 Think About It!

- Handout 3.2 Writing for The New Canadian

- Handout 3.3 Austin Taylor’s Statement in The New Canadian

- Handout 3.4 Letter Writing Rubric

- Handout 3.5 Viewpoints of Dispossession

- Handout 3.6 Mock Question Period

- Handout 3.7 A Promise Broken

- Handout 3.8 Did the Federal Government Act in Good Faith?

- Handout 3.9 Continuum Debate

- Handout 3.10 Letters of Protest

- Handout 3.11 The Custodian’s Response

Sources

- Source 3.1 War Measures Act (1914)

- Source 3.2 Order-in-Council PC 1665

- Source 3.3 Notice to All Japanese Persons

- Source 3.4 Order-in-Council PC 2483

- Source 3.5 The New Canadian, 6 April 1942

- Source 3.6 Memo Angus to King

- Source 3.7(a) Memo: MacNamara to Collins

- Source 3.7(b) Memo: MacNamara to Coleman

- Source 3.8 Memo McPherson to Coleman

- Source 3.9 Dispossession Backgrounder

- Source 3.10 Vancouver Sun, 24 July 1942

- Source 3.11 Vancouver Town Planning Council Meeting Minutes

- Source 3.12 Vancouver Sun, 15 July 1942

- Source 3.13 MP Ian Mackenzie’s Speech

- Source 3.14 Memo: Barnett to Murchison

- Source 3.15 Memo: Read to Robertson

- Source 3.16 Notice of Real Estate Sale

- Source 3.17 Map of Properties, Maple Ridge

- Source 3.18 Conference on Japanese Problems

- Source 3.19 Letter of Protest: T. Fukumoto

- Source 3.20 Letter of Protest: R. Tagashira

- Source 3.21 Letter of Protest: A. Suzuki

- Source 3.22 Letter of Protest: T. Hoshiko

- Source 3.23 Letter of Protest: U. Oikawa

- Source 3.24 Letter of Protest: H.K. Naruse

- Source 3.25 Letter of Protest: S. Odagaki

- Source 3.26 Letter of Protest: R. Yoneyama

- Source 3.27 Reply to T. Fukumoto

- Source 3.28 Reply to R. Tagashira

- Source 3.29 Reply to A. Suzuki

- Source 3.30 Reply to T. Hoshiko

- Source 3.31 Reply to U. Oikawa

- Source 3.32 Reply to H.K. Naruse

- Source 3.33 Reply to S. Odagaki

- Source 3.34 Reply to R. Yoneyama