Offices of Injustice

The dispossession of Japanese Canadians cannot be understood as a single panicked decision in the heat of war. Instead, it involved hundreds of choices that occurred over many years, even after the war had ended.

When Japanese Canadians were uprooted, an office of the federal government called the Custodian of Enemy Property was given control of everything they were forced to leave behind. The office controlled the property of Japanese Canadians starting in 1941, when the government seized fishing vessels, firearms, and radios from Japanese Canadians. In 1952, it sold the last of the property seized from Japanese Canadians and closed its doors, seven years after the war ended.

The Custodian was supposed to protect the property of Japanese Canadians. Instead it served as the headquarters of the dispossession.

Officials rented a floor in Vancouver’s Royal Bank Building and employed more than one hundred staff. They bought rows of cabinets to file tens of thousands of documents. Records were kept on more than 16,000 Japanese Canadian adults.

The Custodian’s office was busy. Its staff catalogued property, estimated its value, maintained insurance, paid miscellaneous expenses, and wrote a mountain of letters to Japanese Canadians and those interested in their property. They toured neighbourhoods and inspected houses. They warehoused personal belongings and, for a time, they shipped selected items to Japanese Canadians. And then, once the decision was made to sell, they organized appraisals, auctions, and real estate sales .

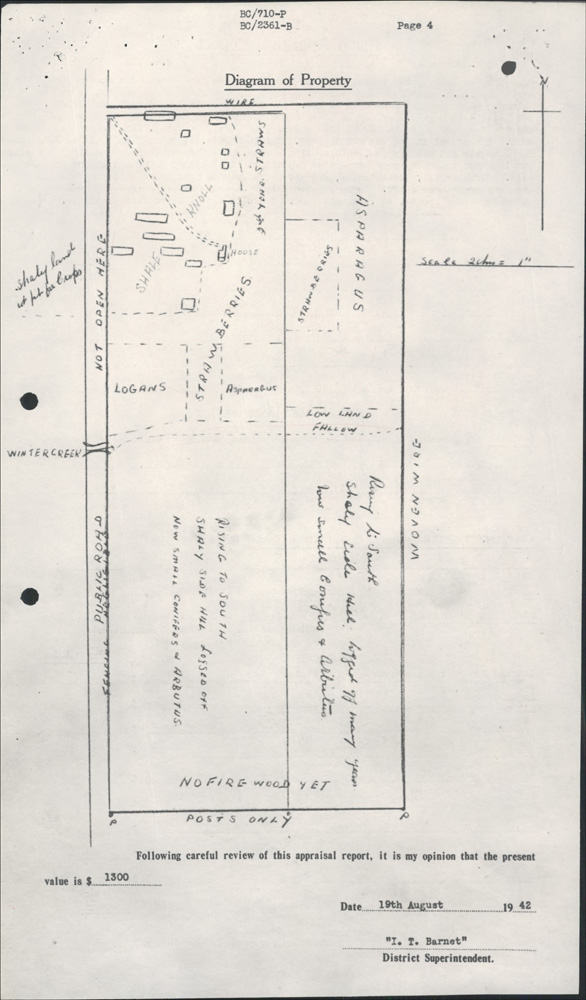

In other government offices, map makers laboured away. Employees of the Soldier Settlement Board sketched hundreds of Japanese Canadian-owned farms in the lower mainland of British Columbia. In 1944, they arranged for the lands to be seized for veterans returning home from the Second World War.

The dispossession was hard work.

Leonard Frank. Jewish Museum and Archives of British Columbia LF.01632

Leonard Frank. Jewish Museum and Archives of British Columbia LF.01632

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, F.G. Shears Papers, box 1, file 1

Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, F.G. Shears Papers, box 1, file 1

Library and Archives Canada, e011167565

Library and Archives Canada, e011167565