Many Losses

Had Japanese Canadians returned to their homes between 1942 and 1949, they would likely have been aghast. They might have caught state officials carting away their belongings. They might have seen a former neighbour stealing their farm equipment. Or they might have witnessed dozens of auction-goers bidding on their kitchenware. Such events were among the daily realities of the dispossession.

Instead, Japanese Canadians were confined to sites of internment. They could only hope that the government would honour its promise to protect what they had left behind.

The government’s handling of Japanese Canadian belongings was disastrous from the start.

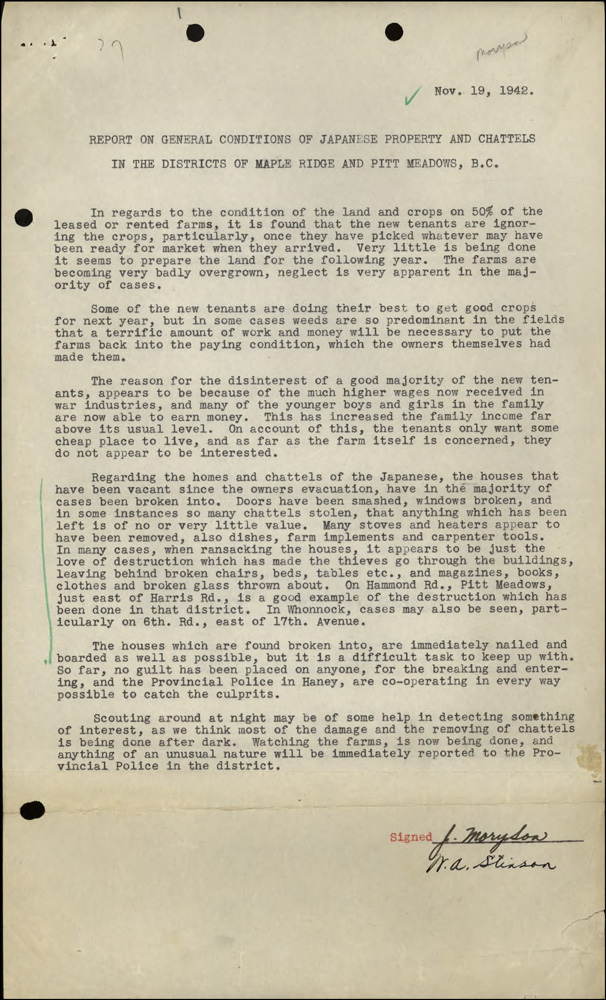

State administers fumbled as they lost Japanese Canadians’ property. They took little action when thieves and vandals targeted Japanese Canadians’ property. One official noted that “almost every building formerly owned by Japanese … has been entered at one time or another.”

After a year of failing to protect the property entrusted to them, officials decided to sell all of it. They listed almost 2,000 homes, farms, and businesses for sale.

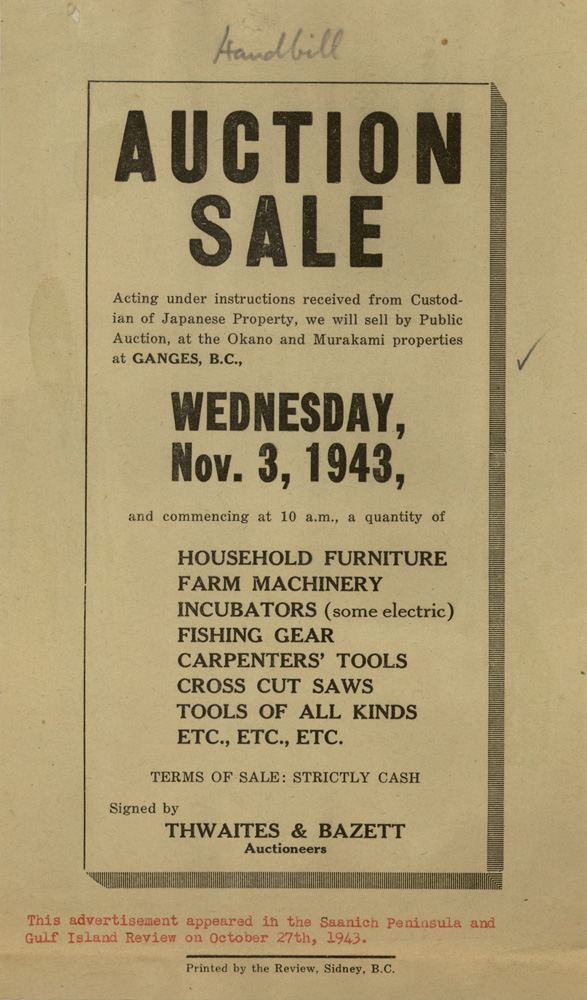

Personal belongings were sold at public auction. Officials let bidders decide the price of fair exchange. The Canadian government held more than 250 public auctions of Japanese Canadian goods between 1943 and 1947. It sold some 90,000 individual items to crowds of eager buyers. Stoves, heaters, kitchen utensils, and breakfast dishes sold briskly. Only those that held little appeal to buyers survived: photo albums, kotos, and family shrines.

Japanese Canadians received receipts of paltry sums for precious heirlooms. It was impossible to replace meaning and value of their personal belongings.

Library and Archives Canada, e01118381

Library and Archives Canada, e01118381

Library and Archives Canada, e011167565

Library and Archives Canada, e011167565